In the first installment, I laid out the general case for money not really working for its intended purposes. In this, I'm going to go far more in-depth on why money doesn't really do what classical economists think it does for a key component of what an economy is supposed to do, namely getting goods and services to the people who need or want them.

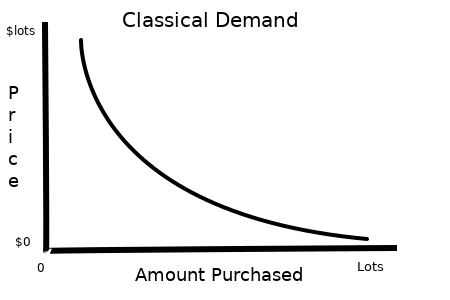

A basic idea of classical economics is concept of demand, which is the amount of money that people are willing to pay to get some product that solves some problem they're having. This in turn is based on a further concept of utility, which is to say the usefulness of those particular products to potential buyers. There's also some math regarding whether there's other products that could do a similar job called substitute goods (e.g. hot dogs instead of hamburgers), and other products that are commonly used with the product in question (e.g. hamburger buns with hamburgers). But in the end, you're left with a relationship between the price and quantity purchased like this:

Following standard economics 101, the price of a product will fall somewhere on that line. In short, the more expensive something is, the less people will buy it, and the cheaper something is the more people will buy.

Alas, that doesn't match how actual people think, at all.

Behavioral economics is all about studying how people actually behave, and it turns out that the classical ideas about demand aren't really all that useful for understanding it. The key conclusion is that most people will divide their purchases into 3 big categories:

A. Stuff They Absolutely Need

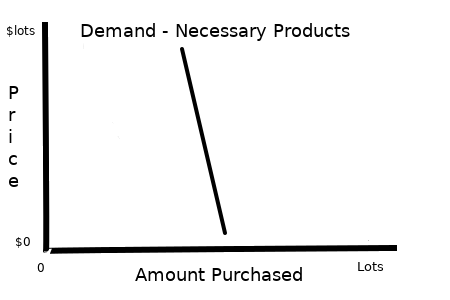

Food. Electricity. Health care. The rent or mortgage payment. A phone. A vehicle and the fuel to run it if that's the only way to get to where they need to go. These are the kinds of things that nearly everybody will pay any price to get, because they are rightfully very scared about what happens when those things are unavailable. There might be variations on how much people will pay, and what kind of services they're going to get for these things, but nobody is willing to do without them.

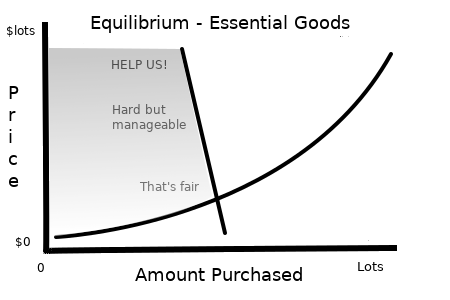

These products are affected by price, because if these items get too expensive some people will be forced to do without them, but it looks very different from the one shown above, because going without is an extreme hardship. One other thing to notice here is that there's a natural limit to how much of this will get sold as a consumer good, because there's very little value in having extra. For instance, in countries where private health insurance is used to manage health care, almost everyone will have at most 1 health insurance policy, because there's no advantage to having 2 policies. Even products where richer people might have more than 1 per person, like cars and homes, there's still limits because even rich people don't gain anything by having more than a few of those items.

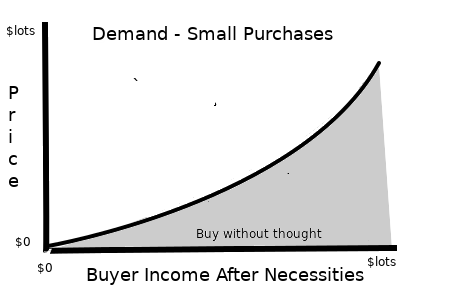

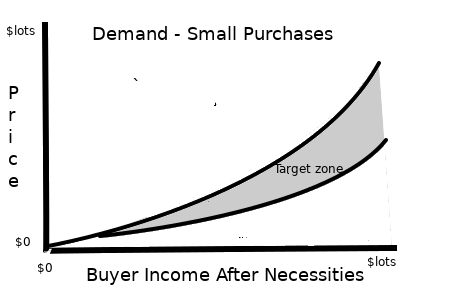

B. Stuff That Is Too Cheap To Think About

A candy bar. A lighter. A fast food meal. A morning cup of coffee. A premium movie on a streaming service. What these all have in common is that they're relatively small purchases of minor luxuries, nice to have, and if you aren't super-poor you can afford them every so often so why not enjoy yourself a bit? Where the line is for things that fit into this category vary quite a bit by income, but a lot of products and even entire industries survive in this niche.

Because these are purchases made without the buyer really thinking about it, the key relationship isn't between price and the amount purchased, but rather the price and the income level of the buyer.

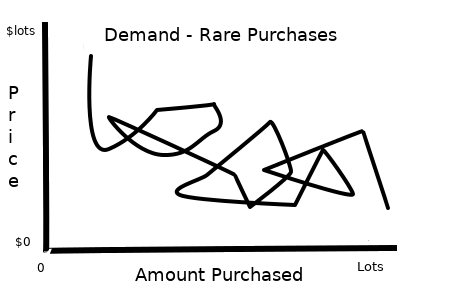

C. Purchases They Think About

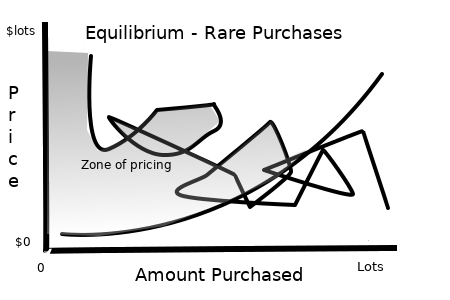

A TV. A kitchen gadget. A new piece of furniture. A musical instrument. A computer or smartphone. What these have in common is that they aren't absolute necessities, they're certainly nice to have if you can get them, but they're also pricey enough that you aren't just going to buy them without a second thought. These products frequently will have quite a range of features and prices, which are likely to be extremely confusing.

This intentional confusing of the issue leads to buyer behavior that can look, well, confused.

A key thing to know is that manufacturers of consumer products know exactly which niche they are in, and that dramatically affects how their products are priced, marketed and sold.

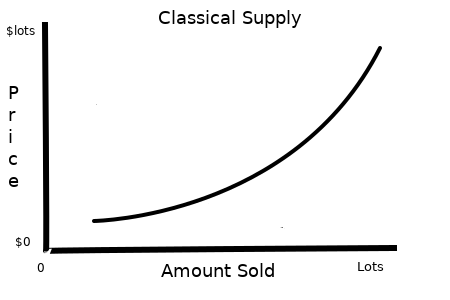

The second really big idea of classical economics is concept of supply, which is the amount of money that producers of a product are willing to accept for a product. This in turn is driven by the marginal cost of production, in other words how much a manufacturer needs to spend in order to make 1 more widget once their production line is set up. There's additional math about how much it costs to set up that production line (barrier to entry), and also regular efforts to adjust supply chains and tweak designs to use cheaper materials and/or labor. But in the end, you're left with a graph showing the price and quantity sold like this:

Following standard economics 101, the price of a product will fall somewhere on that line.

Following standard economics 101, the price of a product will fall somewhere on that line.

Alas, as you might have guessed from the previous section, this is wrong too.

There are some major difficulties with the classical economic theory, but they're all rooted in one problem: If the price of the product falls on the supply line drawn above, there's no profit to be made. The CEO might get paid a reasonable salary for their time, but the company that sells items along that supply line isn't going to make enough money to pay that CEO millions and/or pay out large dividends to investors and/or reinvest the money into stock buybacks. So that supply line doesn't really set what the price will be, only the lowest the price will be.

Classical economic theory says that businesses are prevented from overcharging because of the threat of a new competitor coming in and selling the same thing but cheaper. But that's just not true for most businesses today, because the cost of setting up manufacturing and distribution on a scale that can handle the load is too high for a new player to enter the market. That leaves either a handful of businesses supplying the goods in question, or even a monopoly, possibly enforced by law via patents and copyrights. And those handful of businesses would be generally perfectly content to all overcharge for their products, because they all can make more money by overcharging a smaller number of customers than they can having a price war and driving the price down. There is some math involved about whether it's beneficial for the smallest company in the market to try to undercut one of the larger companies on price, but more often than not the answer is to avoid price competition.

And that means that the main pressure to keep prices low come not from competitors, but solely from the psychological forces that control consumer demand.

According to classical economics, the supply and demand behaviors of sellers and buyers mean that the sellers will produce as much of the product in question as the buyers are willing to pay for. In short, the classic graph that looks like this:

However, as I hope this has demonstrated, neither buyers nor sellers actually work that way. Instead what happens is that sellers know which of the 3 psychological niches of the buyers their product falls into, and adjusts their pricing and marketing to match.

A. Stuff the Buyer Absolutely Needs

Since a buyer absolutely needs these items, the only real pressures on price are (a) whether the public relations of a price will get bad enough that the government starts responding with regulations or price controls, (b) whether it gets so expensive that buyers can't actually afford it and do without instead, or (c) whether it gets so expensive that alternatives start looking like an option. Sellers want to maximize their base price while avoiding these problems, so they will often set up discounting and financial aid systems, loan programs, or government assistance for consumers to pay for the specific item in question. The discounting and financial aid and government assistance very likely will exist more in theory than in reality, and lots of people who should be eligible for it won't get it, but anytime a company is accused of price gouging an essential item they will point to these programs as the reason why their prices are not inhumane.

These products aren't usually advertised all that heavily. They don't need to be: You don't need to go through extensive psychological efforts to convince somebody that they want a roof over their head, for example. The major exception to the "no marketing" rule is pharmaceuticals and medical devices to treat ailments that many people who have them don't know they have or don't know there's available treatment for them, because that expands the people who believe they absolutely need the product in question.

B. Stuff Too Cheap To Think About

B. Stuff Too Cheap To Think About

The key to selling these products is make the products available absolutely everywhere. In schools. In your workplace. In every tiny convenience store and gas station. Even within your own home, if it's something that can be provided online. This is because most purchases of these products are on impulse, and depend on "You can have this right now! Don't think, just buy!"

The pricing of these products aims to be just low enough that you don't start thinking about the price. For the average person, there's not a major difference between a $2.19 product and a $2.29 product, but multiply that extra dime by millions of units sold and you'll realize that the seller is taking that difference very very seriously.

These products are advertised extremely heavily, with the goal that you will associate them with feeling good about life. Techniques for this include bright or pastel colors, sexually attractive people, scenes of partying and dancing, and energetic or warm music. Sellers think very carefully about what income bracket they are targetting for these items, and adjust their marketing and pricing accordingly, even though the cost of making the item is frequently far lower than what they are selling it for.

C. Purchases Buyers Think About

Now we're getting into some of the harder products to sell. Buyers are going to sit down and try to compare features, prices, consider what they're budget looks like, and if the market is competitive enough they'll actually make the optimal decision. But the optimal decision from the buyer is the last thing a seller wants - that cuts down on profits - so they have to take a different approach.

And the different approach is fairly simple: Confuse the buyer. Use jargon, come up with feature names that no ordinary person can understand, and have so many variations on the product in question that the buyer loses sight of the features that actually matter and instead judge more on things that doesn't really affect its usefulness or cost to produce it such as shape, color, brand, or cupholders.

While some of these products are advertised, the goal of that advertising is to associate the product with the brand, and create certain emotional associations towards the product in the minds of buyers. For instance, car ads will regularly show a professional driver zooming along a closed-course country road, but will never ever show a busy worker stuck on a busy freeway during their morning commute, all in an effort to make viewers of those ads associate the car with a sense of "freedom".

How Knowing All This Can Help You

How Knowing All This Can Help YouAs a buyer of consumer goods, your basic goal is to maximize what you get while minimizing the price you pay. And the key to doing that effectively is to ignore as much irrelevant information as possible when making your buying decisions, and use your brain before using your wallet.

For products that you view as necessities, it's worth periodically going through the mental exercises of "What happens if I don't get this?", "Where else might I be able to get this?", and "What other ways do I have of handling this problem?" The first question might get you realizing that something that you may be treating as a necessity (e.g. basic cable) isn't actually necessary. The second question will encourage you to periodically comparison-shop and see that a competitor might be able to get you the same thing significantly cheaper. The third question will encourage you to look for cheaper solutions, e.g. an older generic pill rather than the newer name-brand pill.

For products that you aren't thinking about cost when you buy them, the basic rule is "don't buy them, or opt for generics over brand names and buy in larger quantities." So, for instance, if you have a habit of eating a small bag of potato chips as part of your lunch, buy large bags or even bulk quantities and pack a small baggie in the morning, and you'll save a significant amount over the course of a month. And the simple act of switching from a brand-name to a no-name or store brand can cut your costs by 50% or more. Also, if you are going to buy a small single item on impulse, look for items priced ending in a number other than "0" or "9", which is one indication they might be priced based on cost rather than psychology.

For bigger purchases that you need to think about, start the process by identifying what you are looking for, and what problems you expect this product to solve for you. Do not look at what's on the market until you know what *you* actually want. Then look for used options to see if there's something there that can meet your needs, and only then new items on the market. And very simply, you want the cheapest one that meets the specifications you started with and has decent ratings for durability and reliability from online boards. Also, do not opt for warranties or insurance offerings, as those usually do not pay off.

These kinds of decisions will help you limit what you are paying for the things you are buying to the actual cost of providing those things, rather than paying for shareholder profits and CEO salaries.

And more abstractly, it is worth thinking about what percentage of your spending goes to not the production and distribution of stuff you need, but to changing your beliefs about those products. Entire departments of most major corporations are dedicated precisely to this task, and yet none of them change what the actual stuff in question is or how it might help you.

Comments

There are currently no comments

New Comment